“That Ain’t In The Big Book” or” MOST COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS IN A.A.”

I found this article on-line about AA and The Big Book. I have picked it apart. It is rich and full of lots of great information. The red text is my commentary on the article. There are many misconceptions about whats in the Big Book passed down from generation to generation. This article clears up many of the most common. A.A. and prayer are how I got sober its not perfect and I would not fit in if it were.

The problem with this article found at http://www.nwarkaa.org/aintinthebook.htm is that the writer is unable to see that sometimes there are two right answers to one question, it can be both. Two rights don’t make a wrong. Not everything is black and white there are circumstances that change therefore reactions change. The writer is also right about several of his A.A. misconceptions.

That ain’t in the Big Book article starts here, my comments are in red.

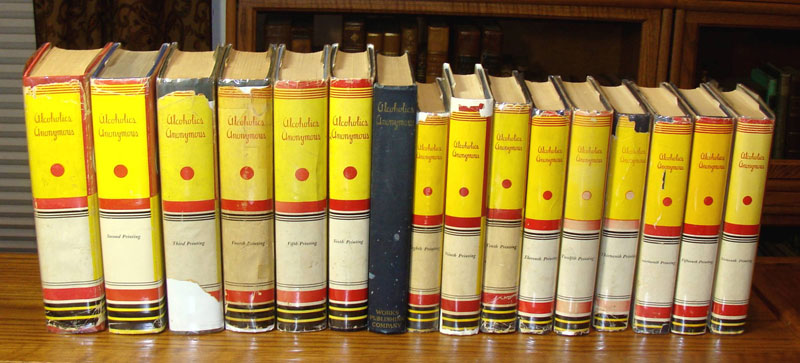

THAT ISN’T IN THE BOOK! WE HEAR A LOT OF STUFF SAID IN MEETINGS THAT CAN’T BE RECONCILED WITH THE PROGRAM AS DESCRIBED IN THE BIG BOOK OF ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS. WHAT FOLLOWS ARE SOME OF THE THINGS WE OFTEN HEAR, ALONG WITH WHAT THE 1ST EDITION OF OUR BASIC TEXT HAS TO SAY ON THE SUBJECT. (Some versions of the Big Book will not line up page for page with this article like the 80 year red and yellow cover paperback, however most will)

“Remember your last drunk”

Page 24, Paragraph 2: “We are unable, at times, to bring into our consciousness with sufficient force the memory of the suffering and humiliation of even a week or a month ago. We are without defense against the first drink.” (Not a contradiction What Bill is talking about here is when we are still in our disease we are in denial hence: we block out the bad memories best we can. )

____________________________________________________________

“I choose not to drink today”

Page 24 Paragraph 2: “The fact is that most alcoholics, for reasons yet obscure, have lost the power of choice in drink.” (Again same thing: Not a contradiction What Bill is talking about here is when we are still in our disease we have no power of choice but clearly when we work the steps choice returns UNTIL we put alcohol in our bodies and the allergy awakens, then we are slaves once again to the whims of demon alcohol)

____________________________________________________________

“Play the tape all the way through”

Page 24, paragraph 3: “The almost certain consequences that follow taking even a glass of beer do not crowd into the mind to deter us. I f these thoughts do occur, they are hazy and readily supplanted with the old threadbare idea that this time we shall handle ourselves like other people. There is a complete failure of the kind of defense that keeps one from putting his hand on a hot stove.” (Once again, once we are sober go through re-hab and are in A.A. we are able to pull up the necessary memories of bad consequences which WILL detour us from the drink.)

___________________________________________________________________

“Think through the drink”

Page 43, paragraph 4: “Once more: The alcoholic at certain times has no effective mental defense against the first drink. Except in a few rare cases, neither he nor any other human being can provide such a defense. His defense must come from a Higher Power.” Once we are sober we can “play it through” and “go to a meeting” (my guess is this writer is justifying a relapse by the use of the literature and the conception of powerlessness he is using the Big Book to continue drinking, ironic no doubt remember we addicts are very intuitive and we must justify our actions or the guilt will kill us.)

______________________________________________________________________

“I will always be recovering, never recovered.”

Title Page: “ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS. The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women Have Recovered from Alcoholism” (I totally agree with him on this one we absolutely do recover, at least I have.)

Page 20, paragraph 2: “Doubtless you are curious to discover how and why, in face of expert opinion to the contrary, we have recovered from a hopeless condition of mind and body. (here, here!)

Foreword to the First Edition: “We, of Alcoholics Anonymous, are more than one hundred men and women who have recovered from a seemingly hopeless state of mind and body.”

Page 29, paragraph 2: “Further on, clear-cut directions are given showing how we recovered.”

Page 132, paragraph 3: “We have recovered, and have been given the power to help others.”

_______________________________________________________________________________

“We are all just an arms length away from a drink”

Page 84, paragraph 4, “And we have ceased fighting anything or anyone – even alcohol. For by this time sanity will have returned. We will seldom be interested in liquor. If tempted, we recoil from it as from a hot flame. We react sanely and normally, and we will find that this has happened automatically. We will see that our new attitude toward liquor has been given us without any thought or effort on our part. It just comes! That is the miracle of it. We are not fighting it, neither is we avoiding temptation. We feel as though we had been placed in a position of neutrality – safe and protected. We have not even sworn off. Instead, the problem has been removed. It does not exist for us”

_____________________________________________________________________________

“I don’t have an alcohol problem, I have a living problem”

Page xxiv, paragraph 2: “In our belief, any picture of the alcoholic which leaves out this physical factor is incomplete.” (hmm I don’t really see this as a contradiction, I believe in “underlying causes of addiction and the struggle with life on life’s terms why would a living problem be discounted because it’s an allergy. Again it’s both, I have the allergy that is now in check by staying sober but also I have an underlying emotional disorder which affects my living when sober at times which is fixable by the way”)

______________________________________________________________________

“Don’t drink and go to meetings.”

Page 34, paragraph 2: “Many of us felt we had plenty of character. There was a tremendous urge to cease forever. Yet we found it impossible. This is the baffling feature of alcoholism as we know it—this utter inability to leave it alone, no matter how great the necessity or the wish.” (Come on writer your just fishing for ways to put down the program. By our support group the 12 steps and meetings we now have a way to not drink and go to meetings.)

Page 34, paragraph 3: “Whether such a person can quit upon a nonspiritual basis depends upon the extent to which he has already lost the power to choose whether he will drink or not.” (some are just problem drinkers and can quit)

Page 17, paragraph 2: “Unlike the feelings of the ship’s passengers, however, our joy in escape from disaster does not subside as we go our individual ways. The feeling of having shared in a common peril is one element in the powerful cement which binds us. But that in itself would never have held us together as we are now joined.”(sorry I don’t get the connection here I’m lost on this one writer says it contradicts “don’t drink and go to meetings” Isn’t Bill just saying camaraderie isn’t enough to stay sober?)

__________________________________________________________________________

“This is a selfish program” (Totally agree with the writer here. The program is NOT SELFISH rather it is selfless. The 12 Steps are built on self-examination and a truthful self-awareness achieved initially by step 3 “Made a decision to turn our will and our life over to the THE CARE of God as we understood God”. Selfish: means: taking from others, I want, want, want give me give me give me now! Where-as self-examination and self-inventory are humble and are made of humility a spiritual principle that does not fall under the heading of “selfish” this contradiction is based on mistaken definitions and semantics the writer doesn’t know the difference between humility and selfishness, that’s actually pretty common in AA)

Page 20, paragraph 1: “Our very lives, as ex-problem drinkers depend upon our constant thought of others and how we may help meet their needs.”

Page 97, paragraph 2: “Helping others is the foundation stone of your recovery. A kindly act once in a while isn’t enough. You have to act the Good Samaritan every day, if need be. It may mean the loss of many nights’ sleep, great interference with your pleasures, interruptions to your business. It may mean sharing your money and your home, counseling frantic wives and relatives, innumerable trips to police courts, sanitariums, hospitals, jails and asylums. Your telephone may jangle at any time of the day or night. “

Page 14-15: “For if an alcoholic failed to perfect and enlarge his spiritual life through work and self-sacrifice for others, he could not survive the certain trials and low spots ahead.”

Page 62, paragraph 2: “Selfishness, self-centeredness! That, we think, is the root of our troubles”

Page 62, paragraph 3: “So our troubles, we think, are basically of our own making. They arise out of ourselves, and the alcoholic is an extreme example of self-will run riot, though he usually doesn’t think so. Above everything, we alcoholics must be rid of this selfishness. We must, or it kill us!”

____________________________________________________________________________________

“Meeting makers make it” (Please writer not a contradiction, going to meetings is a vital part of recovery. And thrown in with the steps and the fellowship it’s all working toward our recovery. TWO RIGHTS DO NOT MAKE A WRONG! THEY ARE JUST TWO RIGHTS. The writer is stuck in the mind-set of false comparisons and competitiveness. As if recovery was a math test that only has one possible correct answer to every question. Recovery questions often have several good and correct answers. That’s the epitome of the open-minded knowing there can be several right answers and many good things to do.) And often where relapse is concerned “the good can be the enemy of the best in early recovery. If I neglect working the steps and going to meetings to go to work or spend time with my children…seems good right? After all how could anyone tell me not to spend time with my children who I neglected for so long? Early recovery is not the time for good deeds, often good deeds are the precise sabotage our disease will use to make us relapse.)

Page 59, paragraph 3: “Here are the steps we took, which are suggested as a program of recovery”

_________________________________________________________________________

“I’m powerless over people, places and things” (Agreed) I have choices and power the power to heal and the power to hurt and much more. Otherwise I am a leaf in the wind.) We doubtful never were 100% powerless I said 100%.

Page 132, paragraph 3: “We have recovered, and have been given the power to help others.”

Page 122, paragraph 3: ” Years of living with an alcoholic is almost sure to make any wife or child neurotic. “

Page 82, paragraph 4: “The alcoholic is like a tornado roaring his way through the lives of others. Hearts are broken. Sweet relationships are dead. Affections have been uprooted. Selfish and inconsiderate habits have kept the home in turmoil. We feel a man is unthinking when he says that sobriety is enough.”

Page 89, paragraph 2: “You can help when no one else can. You can secure their confidence when others fail.”

_________________________________________________________________________

“You’re in the right place” (Ok some people don’t belong in AA)

Page 20-21: “Then we have a certain type of hard drinker. He may have the habit badly enough to gradually impair him physically and mentally. It may cause him to die a few years before his time. If a sufficiently strong reason – ill health, falling in love, change of environment, or the warning of a doctor – becomes operative, this man can also stop or moderate, although he may find it difficult and troublesome and may even need medical attention.”

Page 31, paragraph 2: ” If anyone who is showing inability to control his drinking can do the right- about-face and drink like a gentleman, our hats are off to him.”

Page 31-32: “We do not like to pronounce any individual as alcoholic, but you can quickly diagnose yourself. Step over to the nearest barroom and try some controlled drinking. Try to drink and stop abruptly. Try it more than once. It will not take long for you to decide, if you are honest with yourself about it. It may be worth a bad case of jitters if you get a full knowledge of your condition.”

Page 108-109: “Your husband may be only a heavy drinker. His drinking may be constant or it may be heavy only on certain occasions. Perhaps he spends too much money for liquor. It may be slowing him up mentally and physically, but he does not see it. Sometimes he is a source of embarrassment to you and his friends. He is positive he can handle his liquor, that it does him no harm, that drinking is necessary in his business. He would probably be insulted if he were called an alcoholic. This world is full of people like him. Some will moderate or stop altogether, and some will not. Of those who keep on, a good number will become true alcoholics after a while.”

Page 92, paragraph 2: “If you are satisfied that he is a real alcoholic”

Page 95, paragraph 4: “If he thinks he can do the job in some other way, or prefers some other spiritual approach, encourage him to follow his own conscience.”

____________________________________________________________________________

“If an alcoholic wants to get sober, nothing you say can make him drink.” (Sure our words affect people and we are affected by others words, false pride loves to say different because we often learn that it’s weak or inferior to allow a person to effect our emotions but hey, we can harden our hearts by blocking people out and not letting them close . Or we can try to guard over our hearts but usually that just amounts to a big pot of denial. We are human and we are supposed to be affected. We have emotions and that we are powerless over but if we work the steps we can heal and become way less prone to feelings of inferiority and fear which trigger hurt then anger then wrath and resentment.)

Page 103, paragraph 2: “A spirit of intolerance might repel alcoholics whose lives could have been saved, had it not been for such stupidity. We would not even do the cause of temperate drinking any good, for not one drinker in a thousand likes to be told anything about alcohol by one who hates it.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

“We must change playmates, playgrounds, and playthings” Again this is more vital during early recovery things change we change when we have some program in us.

Page 100-101: “Assuming we are spiritually fit, we can do all sorts of things alcoholics are not supposed to do. People have said we must not go where liquor is served; we must not have it in our homes; we must shun friends who drink; we must avoid moving pictures which show drinking scenes; we must not go into bars; our friends must hide their bottles if we go to their houses; we mustn’t think or be reminded about alcohol at all. Our experience shows that this is not necessarily so. We meet these conditions every day. An alcoholic who cannot meet them, still has an alcoholic mind; there is something the matter with his spiritual status. His only chance for sobriety would be some place like the Greenland Ice Cap, and even there an Eskimo might turn up with a bottle of scotch and ruin everything!”

_____________________________________________________________________________

“I’m a people pleaser. I need to learn to take care of myself” People pleaser’s don’t want to hurt people’s feelings, we/they want people to like them and maybe fear people not liking them It doesn’t mean that we are always being a self-seeker however the words “human” and “self-seeker” are synonymous to an extent. If not, the human race wouldn’t survive. We must be self-seeking to survive. But we also help others. Is it not possible that both are present and even necessary during certain actions…of coarse it is. We give and we take. The program is a giving and a taking program they are both right. Service and step 12 is giving and step 2, 3, and 11 are taking or a better word is “receiving”. We counsel others and then we receive counsel or suggestions same thing both right. In meetings we take what we need. We also give in meetings when we share. Why would it have to be only one way? Who made that rule?

Page 61, paragraph 2:”Is he not really a self-seeker even when trying to be kind?”

____________________________________________________________________________________________

“Don’t drink, even if your ass falls off.” (again with the program we an “not drink” I am not sure why the writer saw this as a bullshit cliche’ except he is fishing to make something wrong and I can totally relate to that. Sometimes I am just in that negative mind-set, our writer may be doing very well in his/her recovery right now. This article does not make him a bad person he may have moved on quite well after this article. idk We should not harshly judge a man by one article.)

Page 34, paragraph 2: “Many of us felt we had plenty of character. There was a tremendous urge to cease forever. Yet we found it impossible. This is the baffling feature of alcoholism as we know it—this utter inability to leave it alone, no matter how great the necessity or the wish.”

______________________________________________________________________________________________

“I haven’t had a drink today, so I’m a complete success today.” ( or the way I always hear it is “I didn’t drink today so today is a good day!” I agree with our writer: total bull shit. Do people really believe this? However in all open-mindedness. That cliché is used for people in early recovery who need badly to feel better and this is a splendid justification of everything they have done up and until the point that they say it. It’s all good, everything is OK, its kind of a reassuring statement that we are not going to fall apart and that our feelings at the time are not going to define or kill us so, “bullshit “as it may be it helps people and that’s OK by me. Why the opinion you might ask? Because I am a realist who has had plenty of shitty days, great days, and fair days sober so please after 10 years you will most likely agree with me. There are bad days, good days and average days it’s called “balance” emotional balance. Then again, it all depends on your definition of a “good day”. One man’s truth is another man’s bullshit. And one thing certain some AAers lover to re-define the English language. So good day does not mean good day any more it actually now means “sober day.” People die, people o.d, people betray, people hurt, kill and cuss you out not every day will be a good day and if we believe that story we are setting ourselves up for failure. Comparing other peoples outsides to my insides. Why am I not happy joyous and free all the time like Hugo portrays? I must not be working my program right. What’s wrong with me? You catch my drift? That’s why our sometimes closed minded writer put this one on his list.

Page 19, paragraph 1: “The elimination of drinking is but a beginning. A much more important demonstration of our principles lies before us in our respective homes, occupations and affairs.”

———————————————————————————

“It’s my opinion that…” or “I don’t know anything about the Big Book, but this is the way I do it…” (False humility- the act of dishonest and degrading statements about one’s self which we know are not true) Have you read the Big Book and worked the steps? Then you have something to offer don’t you. Please don’t pretend you don’t. Humility-Awareness of one’s own flaws of character as patterns/ with this knowledge and the tools we can avoid committing our old patterns of character flaws. hence steps 6 & 7

Page 19, paragraph 1: “We have concluded to publish an anonymous volume setting forth the problem as we see it. We shall bring to the task our combined experience and knowledge. This should suggest a useful program for anyone concerned with a drinking problem.”

__________________________________________________________________

“Don’t drink, no matter what.” (Our writer has resorted to Sarcasm–the inability to communicate on an honest level for fear if we reveal our true self and we won’t be liked. so we have learned to communicate with untruths) Sarcasm is rarely literal or true. He knew what Bill meant by this and is pretending he doesn’t. Yes we came to AA to stay sober so we are encouraged to not drink and encourage others to not drink no matter what. If a man doesn’t know if he is alcoholic then he can try the test of limiting his drinking.

Page 34, paragraph 2: “Many of us felt we had plenty of character. There was a tremendous urge to cease forever. Yet we found it impossible. This is the baffling feature of alcoholism as we know it—this utter inability to leave it alone, no matter how great the necessity or the wish.”

Page 31, paragraph 4: “We do not like to pronounce any individual as alcoholic, but you can quickly diagnose yourself. Step over to the nearest barroom and try some controlled drinking. Try to drink and stop abruptly. Try it more than once. It will not take long for you to decide, if you are honest with yourself about it. It may be worth a bad case of jitters if you get a full knowledge of your condition.”

__________________________________________________________________________________

“We need to give up planning, it doesn’t work.”

Page 86, paragraphs 3-4: “On awakening let us think about the twenty-four hours ahead. We consider our plans for the day. Before we begin, we ask God to direct our thinking, especially asking that it be divorced from self-pity, dishonest or self-seeking motives. Under these conditions we can employ our mental faculties with assurance, for after all God gave us brains to use. Our thought-life will be placed on a much higher plane when our thinking is cleared of wrong motives. In thinking about our day we may face indecision. We may not be able to determine which course to take. Here we ask God for inspiration, an intuitive thought or a decision. We relax and take it easy. We don’t struggle. We are often surprised how the right answers come after we have tried this for a while.”

“You don’t need a shrink. You have an alcoholic personality. All you will ever need is in the first 164 pages of the Big Book.”

Page 133, 2nd paragraph: “But this does not mean that we disregard human health measures. God has abundantly supplied this world with fine doctors, psychologists, and practitioners of various kinds. Do not hesitate to take your health problems to such persons. Most of them give freely of themselves, that their fellows may enjoy sound minds and bodies. Try to remember that though God has wrought miracles among us, we should never belittle a good doctor or psychiatrist. Their services are often indispensable in treating a newcomer and in following his case afterward.”

____________________________________________________________________________

“AA is the only way to stay sober.” (God, thereapy, and AA) All work)

Page 95, paragraph 4: If he thinks he can do the job in some other way, or prefers some other spiritual approach, encourage him to follow his own conscience. We have no monopoly on God; we merely have an approach that worked with us.

Page 164, paragraph 3: “ Our book is meant to be suggestive only. We realize we know only a little.”

“My sponsor told me that, if in making an amend I would be harmed, I could consider myself as one of the ‘others’ in Step Nine.”

Page 79, paragraph 2 “Reminding ourselves that we have decided to go to any lengths to find a spiritual experience, we ask that we be given strength and direction to do the right thing, no matter what the personal consequences might be.”

_______________________________________________________________________________

“I need to forgive myself first” or “You need to be good to yourself” (Do both not a contradiction. Bill is only guilty of using poor grammatical wording here. Hard on ourself meaning be honest in our self-appraisal and ALWAYS considerate of ourself and others.)

Page 74, paragraph 2 “ The rule is we must be hard on ourself, but always considerate of others.”

_________________________________________________________________________________

“Take what you want and leave the rest” ??

Page 17, paragraph 3: “The tremendous fact for every one of us is that we have discovered a common solution. We have a way out on which we can absolutely agree, and upon which we can join in brotherly and harmonious action. This is the great news this book carries to those who suffer from alcoholism.”

__________________________________________________________________________

“Just do the next right thing” More fishing come on. Do the next right thing and also get guidance.

Page 86, paragraph 4: ” We may not be able to determine which course to take. Here we ask God for inspiration, an intuitive thought or a decision.”

Page 87, paragraph 1: ” Being still inexperienced and having just made conscious contact with God, it is not probable that we are going to be inspired at all times. We might pay for this presumption in all sorts of absurd actions and ideas.”

____________________________________________________________________________

“Don’t make any major decisions for the first year” Ok there is an exception to every rule.

Page 60, paragraph 4: “(a) That we were alcoholic and could not manage our own lives. (b) That probably no human power could have relieved our alcoholism. (c) That God could and would if He were sought. Being convinced, we were at Step Three, which is that we decided to turn our will and our life over to God as we understood Him.”

Page 76, paragraph 2: “When ready, we say something like this: “My Creator, I am now willing that you should have all of me, good and bad. I pray that you now remove from me every single defect of character which stands in the way of my usefulness to you and my fellows. Grant me strength, as I go out from here, to do your bidding. Amen.” We have then completed Step Seven.”

________________________________________________________________________________

“Stay out of relationships for the first year!” I like this one I am in agreement.

Page. 69, paragraph 1: “We do not want to be the arbiter of anyone’s sex conduct.”

Page 69, paragraph 3: “In meditation, we ask God what we should do about each specific matter. The right answer will come if we want it.

Page 69, paragraph 4: “God alone can judge our sex situation.”

Page 69-70:”Counsel with other persons is often desirable, but we let God be the final judge.”

Page 70, Paragraph 2: “We earnestly pray for the right ideal, for guidance in each questionable situation, for sanity, and for the strength to do the right thing.”

____________________________________________________________________________

“Alcohol was my drug of choice” sarcasm again, the loss of choice is when the obsession is active when we are actively drinking.

Page 24, paragraph 2: “The fact is that most alcoholics, for reasons yet obscure, have lost the power of choice in drink.”

_______________________________________________________________________________

“Keep coming back, eventually it will rub off on you” the “rub off” is that if we keep going to meetings something may eventually click and we will become willing to do the suggestions.

Page 64, Paragraph 1: “Though our decision was a vital and crucial step, it could have little permanent effect unless at once followed by a strenuous effort to face, and to be rid of, the things in ourselves which had been blocking us”

____________________________________________________________________________

“Ninety Meetings in Ninety Days” Chronologically impossible back in the day. Not enough meetings.

Page 15, paragraph 2: “We meet frequently so that newcomers may find the fellowship they seek.”

Page 19, paragraph 2: “None of us makes a sole vocation of this work, nor do we think its effectiveness would be increased if we did.”

Page 59, paragraph 3: “Here are the steps we took, which are suggested as a program of recovery”

________________________________________________________________________

“You only work one step a year” “Take your time to work the steps” I never heard this one. I worked the steps in full formally once a year for the first 6 years.

Page 569, paragraph 3: What often takes place in a few months can hardly be brought about by himself alone.”

____________________________________________________________________

Page 63, paragraph3: “Next we launched on a course of vigorous action.” Writer totally took this one out of context.

Page 74, paragraph 2: “If that is so, this step may be postponed, only, however, if we hold ourselves in complete readiness to go through with it at the first opportunity”

Page 75, paragraph 3: “Returning home we find a place where we can be quiet for AN HOUR, carefully reviewing what we have done.”

_____________________________________________________________________

“Make sure to put something good about yourself in your 4th step inventory.” Yes, he’s right that’s not what an inventory is for. However I have heard people lie about their clean time repeatedly saying “all I have is today” when they have years of sobriety. Is it true that we only have one day sober or not? We are not helping the new-comer by saying that we only have one day sober if we really have 5 years. We do not have the right to re-define the English language or to lie in the name of false pride. Please false humility thinks it has to cut itself down and deny any good thing about itself or its considered vain and conceited. Emotionally balanced people don’t lie about their good qualities and put themselves down to make themselves look good. (God that is so ironic.) SO we should not lie about our good qualities. We don’t brag thats another animal all together. It’s almost like many AAers think that if they admit any good thing about themselves they will fall prey to false pride and get drunk immediately. What are the motives? Be truthful. Show the newcomers that things do get better not just in speaker meetings are we permitted to mention our clean date and accomplishments. The “I don’t know shit” routine doesn’t wear well on people put in a position to teach, lead , and sponsor. We are building self esteem, every time I lie about who I am and what I have accomplished it’s a step in the other direction working the other principles. I confess that I sometimes mention my own accomplishments fishing for some validation and encouragement that I am doing well. I get very little of that and my self esteem does sometimes revert to feeling bad or low or wrong, I have my patterns as well which get revealled when we work steps 4-7. That is a quick fifth step to the world.

Page 64 paragraph 3 “First, we searched out the flaws in our make-up which caused our failure.”

Page 67 paragraph 3 “The inventory was ours, not the other man’s. When we saw our faults we listed them.”

Page 71 paragraph 1 “If you have already made a decision, and an inventory of your grosser handicaps, you have made a good beginning.”

_______________________________________________________________________

“You need to stay in those feelings and really feel them.” Bottom line intense feelings need to be explored. They come from somewhere in our past trauma or they are triggered by character flaws developed in our past from either emotional neglect or abuse or trauma. These core issues produce feelings that we want to bury, numb, deny, deflect, or blame others for. Some feelings should be ignored others need explored and expressed by crying, screaming, moaning, guttural sounds. or they will not heal. Sobriety brings them up in an orderly fashion. Women more than men (I guess) need to talk them through and connect them to their core occurances. What happened and how did it make me feel? Journaling first makes talking about it easier. We are a people with deep shame issues. The experts say addiction is a shame based disease. Every healthy AAer I know has had therapy at which time they opened up about these past issues and feelings and actions they were ashamed of.

Page 84, paragraph 2: “When these crop up, we ask God at once to remove them.”

- 125 paragraph 1 “So we think that unless some good and useful purpose is to be served, past occurrences should not be discussed.” Whatever bill was talking about here will not change my experience with this topic. Nobody wants to go back there I get it but when depression and anxiety get to be too much just know expression with an empathic listener is the key to healing and God. Panic attack are from pent up unexpressed tears and there are some feelings that are so deep tears will not touch them that’s why I say guttural sounds. I am so sorry for your pain. My email is info@recoveryfarmhouse.com feel free to email me but put “ATTENTION LORI” in the subject.

____________________________________________________________________________________

“There are no musts in this program.” self explanatory

Now look at all the good we or I got out of this seemingly insulting article putting down A.A. 🙂

Page 99, paragraph 1: “it must be done if any results are to be expected.”

Page 99, paragraph 2: “we must try to repair the damage immediately lest we pay the penalty by a spree.”

Page 99, paragraph 3: “it must be on a better basis, since the former did not work.”

Page 83, paragraph 1: “Yes, there is a long period of reconstruction ahead. We must take the lead.”

Page 83, paragraph 2: “We must remember that ten or twenty years of drunkenness would make a skeptic out of anyone.”

Page 74, paragraph 1: “Those of us belonging to a religious denomination which requires confession must, and of course, will want to go to the properly appointed authority whose duty it is to receive it.”

Page 74, paragraph 2: “The rule is we must be hard on ourself, but always considerate of others.”

Page 75, paragraph 1: ” But we must not use this as a mere excuse to postpone.”

Page 85, paragraph 3: “But we must go further and that means more action.”

Page 85, paragraph 2: “Every day is a day when we must carry the vision of God’s will into all of our activities.”

Page 85, paragraph 2: “These are thoughts which must go with us constantly.”

Page 80, paragraph 1: ” If we have obtained permission, have consulted with others, asked God to help and the drastic step is indicated we must not shrink.”

Page 14, paragraph 2: “I must turn in all things to the Father of Light who presides over us all.”

Page 62, paragraph 3: “Above everything, we alcoholics must be rid of this selfishness. We must, or it kills us!”

Page 144, paragraph 3: “The man must decide for himself.”

Page 89, paragraph 2: “To watch people recover, to see them help others, to watch loneliness vanish, to see a fellowship grow up about you, to have a host of friends – this is an experience you must not miss.”

Page 33, paragraph 3: “If we are planning to stop drinking, there must be no reservation of any kind”

Page 79, paragraph 2: “We must not shrink at anything.”

Page 86, paragraph 2: “But we must be careful not to drift into worry, remorse or morbid reflection, for that would diminish our usefulness to others.”

Page 120, paragraph 2: “he must redouble his spiritual activities if he expects to survive.”

Page 152, paragraph 2: “I know I must get along without liquor, but how can I?”

Page 95, paragraph 3: “he must decide for himself whether he wants to go on”

Page 95, paragraph 3: “If he is to find God, the desire must come from within.”

Page 159, paragraph 3: “Though they knew they must help other alcoholics if they would remain sober, that motive became secondary.”

Page 156, paragraph 3: “Both saw that they must keep spiritually active.”

Page 130, paragraph 2: “that is where our work must be done.”

Page 82, paragraph 3: “Certainly he must keep sober, for there will be no home if he doesn’t.”

Page 143, paragraph 2: “he should understand that he must undergo a change of heart”

Page 69, paragraph 4: “Whatever our ideal turns out to be, we must be willing to grow toward it.”

Page 69, paragraph 4: “We must be willing to make amends where we have done harm”

Page 44, paragraph 3: “we had to face the fact that we must find a spiritual basis of life – or else.”

Page 78, paragraph 3: “We must lose our fear of creditors no matter how far we have to go, for we are liable to drink if we are afraid to face them.”

Page 93, paragraph 3: “To be vital, faith must be accompanied by self sacrifice and unselfish, constructive action.”

Page 43, paragraph 4: “His defense must come from a Higher Power.”

Page 66, paragraph 4: “We saw that these resentments must be mastered”

Page 146, paragraph 4: “For he knows he must be honest if he would live at all.”

Page 73, paragraph 5: “We must be entirely honest with somebody if we expect to live long or happily in this world.”

But Remember… “When the man is presented with this volume it is best that no one tell him he must abide by its suggestions.” page 144, paragraph 3